Mary Slessor-2

Missionary to Africa

Mary Slessor-2 - Mary Sails

For Africa - Chapter 2

|

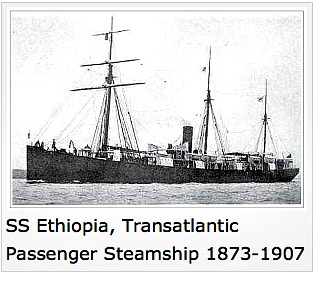

The steamship Ethiopia

Mary Slessor-2 - On a cool autumn morning in 1876, twenty eight year old Mary Slessor stood on the deck of the steamship Ethiopia in

Liverpool docks and waved good-bye to two companions from Dundee who had come to see her

off. As the vessel cleared the land and moved out into the wide spaces of the waters, Mary, who had

always lived in narrow streets, felt as if she were on holiday, and was in as high spirits as any

schoolgirl. She could not help being kind and helpful to others, and soon made friends with many

of the passengers and crew.

|

Mary Slessor-2,

Scottish missionary

to Calabar, Africa

One man drew her like a magnet, for he also was a dreamer of dreams. This was Mr. Thomson,

an architect from Glasgow, who was filled with the idea that the missionaries in West Africa

would do better work and remain out longer if there were some cool place near at hand to which

they could go for a rest and change. He had been all over the Coast, and explored the rivers and

hills, and had at last found a healthy spot five thousand feet up on the Cameroon Mountains,

where he decided to build a home.

He had given up his business, and was now on his way out, with his wife and two workmen, to put his dream into shape. Mary's eyes shone as she listened to his tale of love and sacrifice; but, alas! the plan, so beautiful, so full of hope for the missionaries, came to nothing, for he died not long after landing.

It was from Mr. Thomson that she learned most about the strange country to which she was going. He told her how it was covered with thick bush and forest; how swift, mud-colored rivers came out of mysterious lands which had never been seen by white men; how the sun shone like a furnace-fire, and how sudden hurricanes of rain and wind came and swept away huts and uprooted trees.

He described the wild animals he had seen—huge hippopotami and crocodiles in the creeks; elephants, leopards, and snakes in the forests; and lovely hued birds that flashed in the sunlight—until her eyes sparkled and her cheeks flushed as they had done in the old days when she listened to the stories told by her mother.

Within a week the steamer had passed out of the grey north, and was gliding through a calm sea beneath a blue and sunny sky. By and by Mary was seeking cool corners under the awning, and listening lazily to the swish of the waves from the bows and watching golden sunsets and big bright stars. Sometimes she saw scores of flying-fish hurry-scurrying over the shining surface, and at night the prow of the vessel went flashing through water that sparkled like diamonds.

By and by came the hot smell of Africa, long lines of surf rolling on lonely shores, white fortresses that spoke of the old slave days, and little port towns, half-hidden amongst trees, where she got her first glimpses of the natives, and was amused at the din they made as they came off to the steamer, fearless of the sharks that swarmed in the water. It was all strange and unreal to the Scottish weaver-girl.

|

Mary Slessor-2 in Duke town, Calabar Africa

And when, after a month, the vessel came to the Calabar River and steamed through waters crowded with white cranes and pelicans, and past dark mangrove swamps and sand-banks where the crocodiles lay sunning themselves, and islands gay with parrots and monkeys, up to Duke Town, the queer huddle of mud huts amongst the palm trees that was to be her home, she was excited beyond telling.

At last her dream, which she had cherished through so many long years, had come true, and so wonderful was it that it seemed to be still only a dream and nothing more. Clear above the river and the town, like a lighthouse on a cliff, stood the Mission where "Daddy" and "Mammy" Anderson, two of its famous pioneers, lived. With them Mary stayed until she knew something about the natives and her work. She felt very happy; she loved the glowing sunshine, the gorgeous sunsets, the white moonlight, the shining river, the flaming blossoms amongst which the humming-birds and butterflies flitted, and all the sights and sounds that were so different from those in Scotland. She was so glad that she used to write poems, and in one of these she sings of the beauty of the land: From Dundee to Calabar.

The shimmering, dancing wavelets

And the stately, solemn palms;

The wild, weird chant of the boatmen

And the natives' evening psalms;

The noise of myriad insects

And the firefly's soft bright sheen;

The bush with its thousand terrors

And its never-fading green.

Her spirits, so long bottled up in Dundee, overflowed, and she did things which amused and sometimes vexed the older and more serious missionaries. She climbed trees and ran races with the black girls and boys, and was so often late at meals that Mrs. Anderson, by way of punishment, left her out nothing to eat.

But "Daddy" was fond of the bright-eyed, warm-hearted lassie, and he always hid some bananas and other fruit and passed them to her in secret. There was no factory whistle to warn her in the morning, and sometimes she would start up in the middle of the night and, seeing her room almost as light as midday, would hastily put on her clothes, thinking she had slept in, and run out to ring the first bell, only to find a very quiet world and the great round moon shining in the sky.

It was not long before all the light and colour and beauty of the land seemed to fade away, and only the horror of a great darkness remained. She was taken to the homes and yards of the natives in the town and out into the bush, and saw a savage heathenism that astonished and shocked her. She did not think that people could be so wretched and degraded. At some of the places the naked children were so afraid of her that they ran away screaming. She herself shrank from the fierce men who thronged round her, but her winning way captured their hearts, and she was soon quite at home with them.

When she came back she was very thoughtful, and talked to Mrs. Anderson of the things she had seen. "My lassie," said "Mammy," "you've seen nothing." And she began to tell her of the terrible evils that filled the land with misery and sorrow. "All around us, in the bush and far away into the interior, there are millions of people lost because they’ve never heard the gospel of Christ.

In every little village there is a Chief and a few free men and women, but the rest are slaves, and can be sold or flogged or killed at their owner's pleasure. All the tribes are wild and cruel and cunning, and pass their days and nights fighting each other and dancing and drinking, and there are some that are cannibals and feast on the bodies of those they have slain.

Their religion is the fear of spirits, one of blood and sacrifice, in which there is no love. When a chief dies, do you know what happens to his wives and slaves? Their heads are cut off and they are buried with him to be his companions in the spirit world."

Mary shivered. "It must be awful for the children," she said. "Ah, yes, nearly all are slaves, and their masters look upon them as if they were sheep or pigs. They are his wealth. As soon as they are able to walk they begin to carry loads on their heads, and paddle canoes and sweep and clean out the yards. Often they are beaten or branded with a hot iron, or get their ears cut off. They sleep on the ground without any covering.

When the girls grow up they are hidden away in the house of seclusion, and made very fat. Then they become the slave-wives of the masters or freemen. And the twins! Poor mites. For some reason the people fear them worse than death, and they are not allowed to live; they are killed and crushed into pots and thrown away for leopards to eat. The mother is hounded into the bush, where she must live alone. She, too, is afraid of the twin-babies, and she would murder them if others did not."

Mary cried out in hot rage against so cruel a system. "Oh," she said, "I want to fight it; I want to save those innocent babes." "Right, lassie," replied "Mammy," "and we need a hundred more like you to help."

Mary jumped to her feet. "The first thing I have to do," she said, "is to learn the language. I can do nothing until I know it well." Efik is the chief tongue spoken in this part of Africa, and so quickly did she pick it up and master it that the people said she was "blessed with an Efik mouth"; and then her old dream came true, and she began to teach the black boys and girls in the day school.

There were not many, for the chiefs did not believe in educating them. The bigger ones wore only a red or white shirt, while the wee ones had nothing on at all, and they carried their slates on their heads and their pencils in their hair. In spite of everything they were a happy lot, with bright eyes and nimble feet, and Mary loved them, and those that were mischievous most of all.

She also went down to the yards out of which they came, and spoke to their fathers and mothers about Jesus, and begged them to come to the Mission church. When she had been in Africa for three years she fell ill, and was home-sick for her mother and friends. Calabar then was like some of the flowers growing in the jungle, very pretty but very poisonous. Mary had fever so badly and was so weak that she was glad to be put on board a steamship sailing for Scotland..

In Scotland the cool winds and the loving care of her mother soon made her strong again. Sometimes she was asked to speak at meetings, but was very shy to face people. One Sunday morning in Edinburgh she went to a children's church. The superintendent asked her to come to the platform and speak but she would not. Then he explained to the children that she was a missionary and begged her to tell them something about Calabar. She blushed and refused.

A hymn was sung by the congregation, during which the superintendent pleaded with her to say a few words. "No, no, I cannot," she replied timidly. He was not to be beaten. "Let us pray," he said. He prayed that Miss Slessor might be able to give them a message. When he finished he appealed to her again.

After a pause she rose, and, turning her head half-away to face toward the congregation, she spoke, not about Calabar, but about the free and glad life which children in a Christian land enjoyed, and how grateful they ought to be to Jesus, to whom they owed it all.

When she returned to Calabar again Mary was very happy, for her dream was to be a real missionary, and she found that she was to be in charge of the women's work at Old Town, a place two miles higher up the river, noted for its wickedness. She could now do as she liked, and save more money to send home to her mother and sisters, for they were always first in her thoughts.

|

Mud and bamboo hut

She lived in a hut built of mud and slips of bamboo, with a roof of palm leaves, wore old clothes,

and ate the cheap food of the natives, yam and plantain and fish. Many white persons wondered

why she did this, and made remarks, but she did not tell them the reason: she cared less than ever

for the laughter and scorn of others. There are so many winding creeks that the district looks like a jigsaw puzzle.

She soon became a power in the district. The men in the town were selfish and greedy, and would not let the inland natives come with their palm oil and trade with the factories, and fights often took place, and blood was shed. "This will never do," Mary said, and she began to help the country people, allowing them to come down at night through the Mission ground, guiding them past the sentries to the beach. The townsmen were angry, but they could not scare the brave white woman, and at last they gave in, and trading became free.

Then Mary began to oppose the custom of killing twins, and by and by she came to be known as "the Ma who loves babies." "Ma" in the Efik tongue is a title of respect given to women, and ever after she was known to all, white and black, as "Ma Slessor," or "Ma Akamba," the great Ma, or just simply "Ma," and we, too, may use the same name for her.

|

Like baby Janie

One day a young Scottish trader named Owen came to her with a black baby in his arms.

"Ma," he said, "I have found this baby lying away in the bush. It's a twin. The other has

been killed. She would soon have died if I hadn't picked her up. I knew you'd like her so here she

is."

Ma thanked the young man for his kindness, and took the child, a bright and attractive girl, to her heart of hearts. "I'll call her Janie," she said, "after my sister."

She was delighted one day to hear that the British Consul and the missionaries had at last coaxed the chiefs in the river towns to make a law after their own fashion against twin-murder. This was done through a secret society called Egbo, which was very powerful and ruled the land.

Those who belonged to it sent out men with whips and drums, called runners, who were disguised in masks and strange costumes. When they appeared all women and children had to flee indoors. If they were caught outside, they were flogged. It was these men who came to proclaim the new rules. Ma tells about the scene in a letter to Sunday School children in Dundee.

Just as it became dark one evening I was sitting in my verandah talking to the children, when we heard the beating of drums and the singing of men coming near. This was strange, because we are on a piece of ground which no one in the town has a right to enter. Taking the wee twin boys in my hands I rushed out, and what do you think I saw?

A crowd of men standing outside the fence chanting and swaying. They were proclaiming that all twins and twin-mothers could now live in the town, and if any one murdered the twins or harmed the mothers he would be hanged by the neck. If you could have heard the twin-mothers who were there, how they laughed and clapped their hands and shouted, "Sosoño! Sosoño!" ("Thank you! Thank you!").

Amidst all the noise I wept tears of joy and thankfulness, for it was a glorious day for Calabar. A few days later the treaties were signed, and at the same time a new King was crowned. Twin-mothers were actually sitting with us on a platform in front of all the people. Such a thing had never been known before. What a scene it was! How can I describe it? There were thousands of Africans, each with a voice equal to ten men at home, and all speaking as loudly as they could. The women were the worst. I asked a chief to stop the noise.

"Ma," he said, "how I fit stop them woman mouth?" The Consul told the King that he must have quiet during the reading of the treaties, but the King said helplessly, "How can I do? They be women—best put them away," and many were put away. And the dresses! As some one said of a hat I trimmed, they were "overpowering." The women had crimson silks and satins covered with earrings and brooches and all kinds of finery. The men were in all sorts of uniform with gold and silver lace and jeweled hats and caps.

Many naked bodies were covered with beadwork, silks, damask, and even red and green table-cloths trimmed with gold and silver. Their legs were circled with brass and beadwork, and unseen bells that tinkled as they moved. The hats were immense affairs with huge feathers of all colours and brooches.

|

Egbo warriors

The Egbo men were the most gorgeous. Some had large three-cornered hats with long

plumes hanging down. Some had crowns, others wore masks of animals with horns, and

all were looped round with ever so many colorful skirts and trailed tails a yard or two long with a

tuft of feathers at the end.

Such splendour is barbaric, but it is imposing in its own place. Well, the people have agreed to do away with many of the bad customs they have that hinder the spread of the Gospel. You must remember that it is the long and faithful teaching of God's word that is bringing the people to a state of mind fit for better things. Now I am sleepy. Good-bye. May God make us all worthy of what He has done for us.

The people were good for a time, but soon fell back into the habit of centuries, and did in secret what they used to do openly. Ma saw that the struggle was only just beginning, and she threw herself into it with all her courage and strength.

She was always studying her Bible, and learning more of the love and power of Jesus, and so much did she lean on Him that she was growing quite fearless, and would go by herself into the vilest haunts in the town or far out into lonesome villages.

Often she took a canoe and went up the river and into the creeks and visited places where no white woman had been before, healing the sick, sitting by the wayside listening to the tales of the people, and talking to them about the Saviour of the world. Sometimes there was so much to say and do that she could not get back the same day, and she slept on straw or leaves in the open air, or on a bundle of rags in an evil-smelling hut.

|

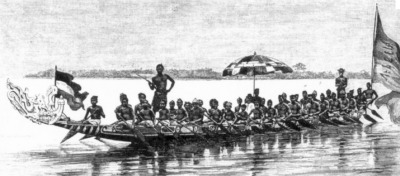

Large canoe to carry Ma

Once she took the children and went a long river journey to visit an exiled chief who lived

in a district troubled by elephants. They were to start in the morning, but things are done very

leisurely in Africa, and it was night before they set off by torchlight. Eyo Honesty VII, the

king of Creek Town, who was a Christian and always very kind to Ma, had sent a State canoe,

brightly painted, with the message:

"Ma must not go as a nameless stranger to a strange people, but as a lady and our mother, and

she can use the canoe as long as she pleases."

There was a crew of thirty-three men dressed only in loin-cloths. As they dipped paddles and sped onwards over the quiet water, a drummer drummed his drum, and the crew chanted a song in her praise: Ma, our beautiful beloved mother is on board, Ho, ho, ho!

The motion of the canoe was like a cradle, and the song like a mother's crooning, and she fell asleep; and all through the night, amongst these native tribesmen, she lay in God's keeping, as safe as a little child.

At dawn they came to a village, where she was given a mud room in the chief's yard, and here for two weeks she lived in the company of dogs, birds, rats, lizards, and mosquitoes. Many of the people had never seen a white person, and were afraid to touch her. She was very sorry for them, they were so poor and naked and dirty, and she busied herself making clothes and offering medicine to the sick. So many were ill that a canoe had to be sent to the nearest Mission House for another supply of medicines.

One day the chief said to her, "Ma, two of my wives have been doing wrong, and they are to get one hundred stripes each on their bare backs. It is the custom." She was horrified. "Why, what have they done?" "They went into a yard that is not their own. Of course," he added, "they are young and thoughtless, they are only sixteen years old, but they must learn." "Oh, but that is a very cruel punishment for young girls." "Ma, it is nothing; we shall also rub salt into the wounds and perhaps cut off their ears. That is the only way to make the women obey us." "No, no, you must not do that," cried Ma. "Bring all the people together for a palaver." The crowd gathered, and the two girls stood in front with sullen faces. Ma spoke to them. "You have done wrong according to your law, and you will have to be punished."

At this, smiles broke over the faces of the men; but Ma turned to them swiftly and cried, "You are in the wrong too. Shame on you for making a law that marries girls so early! Why, these are still children who love fun and mischief. Their fault is a small one, and you must not punish them so cruelly."

The smiles fled, and the faces grew angry and defiant, and there were mutterings and threats. "Who are you to come and spoil our laws," said some of the big men; "the girls are ours, let us have them."

But Ma was firm, and as she was the guest of the village, and worthy of honour, they agreed to give a lighter punishment. The girls were handed over to two strong fellows, who flogged them with a whip. Ma heard their screams amidst the shouts and laughter of those who looked on, and was ready to attend to their bleeding bodies when they ran into her room. Then she gave them something which made them sleep and forget their pain and misery.

"What can you expect?" said she to herself; "they have never heard of Jesus, they worship human skulls, and they don't know about love and compassion and mercy"—and she did her best to teach them. In the quiet nights, when their work in the fields was over, they came and squatted on the ground, the big men in front, the slaves outside, and she stood beside a little table on which were a Bible and hymn-book and a lamp, and in her sweet and earnest voice told them the story of the gentle Jesus.

She could not see anything but the dark mass of their bodies and the gleaming of their eyes, and they sat so still that when she stopped she could only hear the sighing of the wind among the palm tops. It was all very wonderful to them. Sometimes they would ask questions, chiefly about the life after death, which was such a mystery to them, and, when they rose, they slipped away softly to their homes to talk about this strange new religion that was so different from their own. It was the time of storms, and one day when Ma was sewing the sky grew dark, lightning flashed, thunder crashed, and floods fell. The roof of the hut was blown away, and she was drenched to the skin, and for a time was ill with fever and near death.

On the way back at night to Old Town another tornado burst, flooding the canoe, and tossing it about like a match-box on the raging waves. The crew lost their wits, and Ma thought they would be upset. But putting aside her own fear for the sake of others, she made the men paddle into the mangrove swamp, where they jumped into the branches like monkeys and held on to the canoe until the danger was passed. All were sitting in water, and Ma was wet through and shaking with fever. She became so ill that when Old Town was reached she had to be carried up to the Mission House. Yet she did not go to bed until she had made hot tea for the children, and tucked them snugly away for the night.

Soon afterwards another tornado destroyed her house, and she and the children escaped through the wind and rain to the home of some white traders who were very kind to her. But she was so ill after all she had gone through that she was ordered to Scotland, and again had to be carried on board the steamer. She would not leave Janie behind because she was afraid the people would murder her, and so the girl-twin also sailed with her across the sea to Scotland.

Ma soon grew strong in her native air, and one Sunday she went to her old church in Dundee with Janie, and there that morning the little child was given the name that had been chosen for her. With her black skin and solemn eyes she was a curious sight to the boys and girls, and they came crowding round and begged to be allowed to hold her for a little. She appeared at many of the meetings to which Ma went, and during the address would sit on the platform munching cookies, which she was always ready to share with every one near her.

One night Ma travelled to Falkirk to speak to a large class of girls taught by Miss Bessie Wilson, a well-known lady in the Church. She had a message that night, and her face shone and her words fell like stirring music on the young hearts before her. Janie was passed round from one to another, and helped to make her story more real. So delighted were the girls with the baby that they begged to be allowed to give something every month for her support.

Out of that class, six members volunteered to be missionaries in Calabar, Africa, including Miss Wright and Miss Peacock, two of Ma's dearest friends and best helpers.

Ma had a wonderful power of drawing other people to her and of influencing them for good. On this visit one girl, Miss Hogg, was no sooner in her company than she decided to go to Calabar, and she went, and was for many years a much-loved missionary, whose name was familiar to the children of the Church at home.

|

Devonshire cottage

Ma was anxious to be back at her work, but her sister Janie, who was delicate like her brothers,

needed all her care, and was at last ordered by the doctor to live in a warmer climate.

This set Ma

dreaming again. "If only I could take her out to Calabar with me," she mused, "we could live

cheaply in a native hut, and it might save her life." But the Mission Board did not think this

would be right, and Mary, who had a quick brain as well as a warm heart, at once carried Janie

off to Devonshire, that lovely county in the south of England, where she rented a cottage with a

garden and nursed and cared for the invalid.

Very sorrowfully she gave up the work in Calabar she loved so much, but she felt that her sister needed her most. Then she brought down her mother, and they lived happily together, and Janie grew strong in the sunshine and fresh air. After a time Ma thought they could be left, and, after getting an old companion down from Dundee to look after them, she went out again to Africa.

Her new station was Creek Town, a little farther away, where the missionary was her dear friend Mr. Goldie. Here she lived more plainly than ever, for she needed now to send a larger sum of money in order to keep the home in Devonshire. But she had not long to do this loving service, for first her mother, and then her sister, died. All the rest of the family of seven had now passed away, and Ma was alone in the world. She never quite got over her grief and her longing for them all, and to the end of her life was dreaming a sweet dream of the time when she would meet them again in heaven.

With none of her family left to love she began to lavish her affection on the black children, and was specially fond of Janie, who trotted at her side all day and slept in her bed at night. She was a lively thing, full of fun and tricks, and it was curious that the people should be so afraid of her. They would not touch her even if Ma was there. One day a man came to the Mission House who said he was her father. "Then," said Ma, "you will come and see her." "Oh, no," he replied, with fear in his eyes, "I could not." Ma looked at him with scorn. "What harm can a wee girlie do you?" she asked. "Come along." "Well, I'll look from a distance." "Hoots," she cried, and seizing him by the arm dragged him close to the child, who was alarmed and clung to Ma. "My lassie, this is your father, give him a hug."

The child put her arms round the man's neck and he did not mind, and indeed his fierce face grew soft, and he sat down and took her gently on his knee and petted her, and was so delighted with her pretty ways that he would hardly give her up. After that he came often and brought her gifts of food. Thus Ma tried to show the people that there was nothing wrong with twins, and that it was a cruel and senseless thing to kill them.

There were other children, both boys and girls, in the home, whom Ma had saved from sickness or death, and these she trained to do housework and bake and go to market. When their work was done she taught them from their Efik lesson books, and by and by they were able to help her in school and church by looking after all the little things that needed to be done. The oldest was a girl of thirteen, a kind of Cinderella, who was always in the kitchen, but who was very honest and truthful and loved her Ma.

Besides these there were always a number of refugees in the yard-rooms outside, a woman, perhaps, who had been ill-used by her masters and had run away, or girls broken in body and mind, who had been brought down from the country to be sold as slaves and whom Ma had rescued, or sick people who came from far distances to get the white woman's medicine to be healed.

It was a busy life which Ma lived in the African jungle, among the huts and villages of the Creek but she

was happy, like all busy people who love their work and are doing good for God.

Read the rest of the Mary Slessor story

by downloading these FREE pdfs

Mary Slessor Chapter 1

Not a pdf - read it online

More information and FREE

eBooks about Mary Slessor.

What is justification by faith?

From Mary Slessor, return to

Gay Christian 101 Home Page

Grab our FREE

Bible Study downloads

Special thanks to Pat Brush for her editorial

assistance on the Mary Slessor book.

Google Translate

into 90 languages

We are saved:

by grace alone through faith alone

Recent Articles

-

Gay Christian 101 - Affirming God's glorious good news for all LGBs.

Jan 08, 24 12:57 AM

Gay Lesbian Bisexual Christian 101 - Accurate biblical and historical info defending LGB Christians from the anti-gay crowd. -

Romans 1 describes ancient shrine prostitution, not gays and lesbians.

Dec 21, 23 04:37 PM

Romans 1, in historical context, is about ancient Roman fertility goddess worshipers who engaged in shrine prostitution to worship Cybele, not gays and lesbians. -

The Centurion And Pais - When Jesus Blessed A Gay Couple.

Nov 14, 23 10:32 PM

Centurion and Pais? If Jesus blessed a gay relationship, would this change your view of homosexuality?

Bible Study Resources

for eDisciples